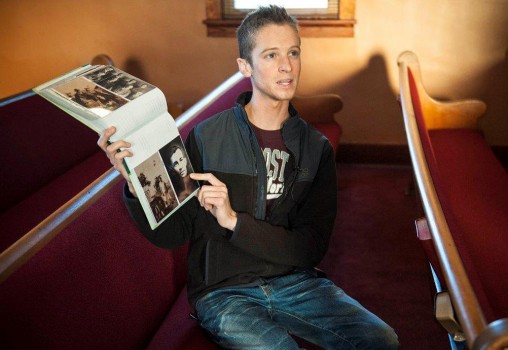

The shadows are growing long in Longtown, Ohio. Connor Keiser cracks open the blinds inside the Bethel Long Wesleyan Church, sending weak shafts of light into the sanctuary. He then settles into a pew, opens a photo album and brings the historic black settlement to life.

The 22-year-old Wright State University student is a direct descendant of James Clemens, a freed slave from Virginia who planted the seeds of Longtown nearly two centuries ago in a rural patch of western Ohio. One of the state’s first black settlements, Longtown became a pioneer in racial integration and a haven for interracial couples.

But today there is little left of the historic community. And if Longtown vanishes, Keiser says, a big part of American history will be lost. So he’s trying to save it.

“A lot of times African-American history isn’t seen as American history. However, it is; it happened,” Keiser said. “We have something very special here.”

Connor Keiser, an international studies major at Wright State, is working to preserve the historic black settlement of Longtown in western Ohio. He is pictured in front of the James Clemens farmhouse. (Photos by Erin Pence)

Clemens and his wife, Sophia, arrived in western Ohio in 1818 and soon became prosperous farmers. Their success attracted many other former slaves, and the community of Longtown — including schools and a church — sprang up near the Clemens farm.

Roane Smothers, a Longtown descendant and president of the Union Literary Institute Preservation Society, says Longtown was one of more than 70 African-American settlements that existed in Ohio before the Civil War. He said about 10 percent of African-Americans were free people of color before the war.

The Union Literary Institute was founded in 1845 near Longtown as a manual-vocational school for students of freed slaves and became one of the first racially integrated establishments of higher education in the nation. It closed in 1914, fell into disrepair and until recently was used to store farm equipment.

Before it was named Longtown, the town was known as the Greenville Negro Settlement. But it needed a different name to establish a post office, so it was named after a respected blacksmith.

Despite its isolation, Longtown did not remain untouched by racism. Keiser said the Ku Klux Klan shot and killed his fourth great-grandfather in 1878.

Today, it is difficult to visualize how much vitality once coursed through the capillaries of Longtown:

- The community was remembered by many people as being the home of a popular tavern.

- Churchgoers would shop around for the best sermon at two churches located across the street from each other. The competition became so intense that one church had to relocate.

- One of Keiser’s great-uncles was a pitcher on the Longtown Tigers semi-professional baseball team, once striking out 21 of the 27 opposing batters he faced.

“The Longtown players weren’t necessarily dark-complected,” Keiser said. “In one particular game, they showed up for the game and the opposing team asked, ‘Where is the colored team?’ They said, ‘We’re right here.’”

In 1880, nearly 1,000 people and hundreds of buildings made up Longtown. Today, only a few buildings and about 50 people remain.

The town’s population began to decline after World War II, when many residents moved to larger cities to find work. Those who remained grew old, many of them died and were buried in one of the town’s three cemeteries, and their children moved away.

Fred Clemens, Keiser’s grandfather, grew up in Longtown, spending more than 40 years of his life there before moving away.

“There used to be a lot of stuff around here. It’s about all gone now,” Clemens said during a recent visit. “It’s something to look back at and appreciate where you come from.”

Keiser — the fifth great-grandson of James and Sophia Clemens — grew up in New Weston, Ohio, 15 miles north of Longtown. But he often visited Longtown, where his grandparents lived.

“We came here on the holidays and on the weekends just to spend time with family,” he said. “It was no different than any other town. I can remember playing out in the pasture with my cousins.”

Keiser’s father is white, his mother black.

“The term ‘colored’ isn’t used a whole lot anymore, but it is here in Longtown. It refers to the ethnic mix that we are here,” he said. “We are of European, African and Native-American blood. The word ‘colored’ encompasses all three of those ethnicities, and that is what I would like to be called.”

The Clemens farmhouse and barn are still standing, but have been ravaged by time, weather and wild animals looking for shelter. Wind and rain have scoured the brick and clawed at the mortar of the farmhouse, which has classical Greek Revival details. Many windows are broken or missing; window openings are sealed with plywood that is beginning to warp. The barn is crowned with a roof of rusting metal.

The Clemens farmstead was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001, an acknowledgement by the federal government that the structures are worthy of preservation.

Keiser, a board member of the Union Literary Institute Preservation Society, is trying to save Longtown by publicizing its history and raising money to renovate and preserve the existing historic structures. He wants to open the Clemens farmstead to the public.

“I’d like to share it because I’m proud,” he said.

On a hallway wall inside the farmhouse are the words “WRJ, 1860,” apparently scrawled by William R.J. Clemens, one of James’ sons. As Keiser walks through the farmhouse, he seems to hear the echoes of history.

“It’s really a hard feeling to describe,” he said. “It’s just amazing to think that my grandparents were here and so much happened in this home over the years. It’s really neat to think that I’m here and I’m able to be here and stand in the home.”

Longtown was a stop along the Underground Railroad, a network of safe houses, churches and shelters instrumental in helping an estimated 30,000 slaves escape to free states and Canada during the 19th century.

“My grandfather was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, so we can probably assume that slaves stopped here for a time,” Keiser said. “There was supposedly a tunnel from the house to the barn.”

This year, the Union Literary Institute received a $17,900 grant from the Ohio History Connection History Fund to help restore the farmstead. With an additional $15,000 from the institute’s preservation society, work is under way to rebuild 18 windows, repair and replace front and side doors, and restore and paint soffits and fascia.

“We’re going to stabilize it the best we can now,” Keiser said. “But we’re going to have to keep raising funds. We are on the road to further saving what we have left.”

But there are still signs of life. The church, which has been rebuilt, holds services every Sunday, attracting as many as 30 congregants. And a recent Longtown homecoming drew about 200 relatives from around the country.

Keiser began his higher education at Edison Community College in Greenville, then went briefly to Wright State’s Lake Campus before transferring to Wright State’s Dayton Campus in September.

“I was drawn to Wright State because of the diversity,” he said. “My major in international studies is tailored toward working with the diverse population that is at Wright State and makes up the world today.”

Keiser became aware of the historical significance of Longtown about three years ago when one of his cousins gave a presentation on the historic community during African-American History Month at the Garst Museum in nearby Greenville.

“The same cousin that I learned my history from had urged me to find my family history, to study it. Because of him I like to say I’m doing what I’m doing,” Keiser said. “I think that the past matters. It’s so empowering to know where you come from, who you come from.”

Smothers said Keiser has given presentations in the area and been very effective in educating the community about the historical significance of Longtown. Keiser’s efforts were recently featured in The Washington Post.

“Many of the African-American farmers and residents of Longtown are dying and their descendants are selling the farms and land to white property owners,” Smothers said. “When this has happened at other African-American settlements, the buildings and cemeteries were demolished and the story about these African-American pioneers are forgotten and buried.”

Keiser refuses to let that happen to Longtown.

“We were so ahead of our time,” he said. “We’ve lived here as a mixed-race community for nearly 200 years and we’ve made it work.”

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business