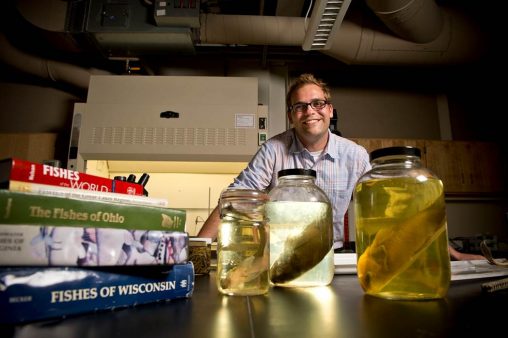

Stephen Jacquemin, associate professor of biology and research coordinator at Wright State’s Lake Campus, led a study documenting changes in water quality following the implementation of new rules and best management practices.

Research at Wright State University’s Lake Campus on the water quality of Grand Lake St. Marys is featured in a prestigious environmental journal and has sparked interest from a watershed group at Lake Champlain in Vermont.

A study led by Stephen Jacquemin, associate professor of biology and research coordinator, was published as the cover story in the January/February issue of The Journal of Environmental Quality. The bimonthly journal covers impacts of human activity on the environment, including terrestrial, atmospheric and aquatic.

The Lake Campus study is titled “Changes in Water Quality of Grand Lake St. Marys Watershed Following Implementation of a Distressed Watershed Rules Package.”

The Lake Campus study documents long-term changes in water quality over the past decade related to nutrient loading from agricultural runoff following a series of rules — such as a ban on the use of manure in the winter — and best management practices that have been implemented beginning in 2011.

Jacquemin and his research team documented overall nutrient reductions at up to nearly 60 percent at most flow conditions for sediment, nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations and loadings.

“The significance of this study is that it demonstrates improvements in a region that for decades only exhibited poor water quality trends and data,” said Jacquemin, a fish ecologist. “This study represents an important starting point to begin other efforts to make more improvements in water quality around the region.”

He said that while the study shows real reductions in nutrient loading and clear improvements in water quality, concentrations are still high and much more work needs to be done.

Jacquemin said the study can serve as a model for other regions, which could implement the practices to improve the quality of their watersheds.

An environmental consulting firm working with the Lake Champlain watershed group has reached out to Jacquemin and his team. Lake Champlain, a natural freshwater lake, drains nearly half of Vermont and supplies about 250,000 people with drinking water.

The consulting firm is exploring what the experiences of the Lake Campus researchers used to construct wetlands — sometimes called treatment trains — to filter out nutrients prior to discharge into lake waters.

The consulting firm is exploring what the experiences of the Lake Campus researchers used to construct wetlands — sometimes called treatment trains — to filter out nutrients prior to discharge into lake waters.

The researchers provided the firm with engineering schematics, layouts and water quality testing data. They also invited the watershed group to visit Grand Lake St. Marys this spring or summer to observe the wetlands, which divert a portion of stream flow into a series of interconnected wetland pools.

“As the water flows through the wetland system, sediment material drops out and nutrients are able to be taken up or transformed by living organisms present in the wetland,” said Jacquemin. “The combination of physical, chemical and biological removal that occurs in the wetlands helps to filter water before it discharges into the lake.”

The formation of the wetlands was spearheaded and financed by the Grand Lake St. Marys Restoration Commission, which works to improve the lake through the cooperation of farmers, landowners and park operators.

Jacquemin said the researchers are particularly motivated by the nutrient removal efficiency and the quantity of flow from several creeks that they have been able to treat.

On average, the researchers have been able to treat one-third of the total stream flow from each creek with treatment trains. That has resulted in removal efficiencies during peak loading periods of late spring and summer of close to 50 percent nitrate removal and 75 percent of the phosphorus.

Jacquemin’s work involves assessing the health of rivers, lakes and streams by using biological indicators such as fish and invertebrates in conjunction with the physical condition of habitat as well as chemical concentrations in the form of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus.

“If an aquatic system is unhealthy or degraded in some way, I work to try to find a path towards remediation,” he said. “To accomplish all of this, I work with a large group of incredibly talented students, staff, faculty and researchers from around the Midwest.”

Jacquemin joined the faculty at Wright State in 2013. Prior to arriving, he interned with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at Okefenokee Swamp, a shallow, 438,000-acre wetland that straddles the Georgia-Florida border.

He later studied environmental management at the University of Havana, joining Cuban marine biologists in doing surveys of large sharks, rays and other fish inhabiting the coastal waters around the island’s coral reefs.

Jacquemin returned to the Midwest and earned his Ph.D. in environmental science from Ball State University in Indiana. He did his dissertation on the evolution of freshwater fish.

Walking through open doors

Walking through open doors  Adventures await

Adventures await  Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers

Wright State to expand nursing facilities to meet workforce needs and prepare more graduates for in-demand careers  Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come

Wright State student-athletes make a lasting impact on local family with more to come  Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business

Wright State names Rajneesh Suri dean of Raj Soin College of Business