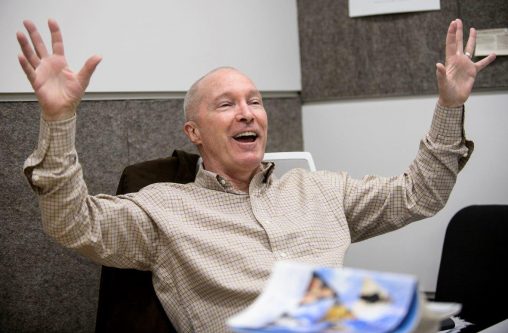

Wright State music and English lecturer Dennis Loranger has developed a reputation for his lively writing in the program notes for the Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra. (Photos by Will Jones)

If you’re taking in a symphony by the Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra, the guy you want to sit next to is Dennis Loranger.

The Wright State University music historian will likely know more about the music and the composer than anyone else. Not only does he have a strong institutional knowledge of the composers, but he does extensive research on them and their music, digging up nuggets of information and offering insight that deepens audience appreciation.

And if you can’t sit next to Loranger, grab a program. He writes the program notes. And he’s developed a reputation for lively writing in a genre not known for it.

In writing about Ludwig van Beethoven’s Third Symphony, Loranger refers to a letter Beethoven wrote to his brothers, bemoaning his gradual loss of hearing. The symphony, said Loranger, marked the beginning of Beethoven’s “heroic” period and took on an intensity of emotion that expressed both adversity and triumph as though his struggles with deafness were given musical form:

“The lower strings, after opening with a simple leaping figure, abruptly swerve into a foreboding mood. That darker and unsettled mood overshadows the rest of the movement, which threatens to burst the bounds of the sonata form.”

In writing about Gustav Mahler’s “Das Lied von Der Erde,” Loranger notes that the composer had suffered a family tragedy and a heart condition. He had taken comfort in a book of Chinese poetry, the world weariness of which helped inspire “Das Lied”:

“The second movement, ‘The Lonely One in Autumn,’ is a slow piece, the voice asking whether love will ever shine again, with the chilly violins apparently answering in the negative.”

Loranger has written program notes for the Dayton Philharmonic’s Classical series since 2007. He has also written program notes for the Yellow Springs Chamber Music series.

“I try to make the composers flesh-and-blood people,” he said.

Loranger said many people who write program notes fail to give enough detail about the composer or the work. For example, program notes about Gioachino Rossini, an Italian composer best known for his operas, may say that Rossini does a great job simply because he’s Rossini.

“That tells me nothing at all except that this guy’s a genius, and that’s not going to make you any more inclined to listen to him,” said Loranger. “But if you were to say here was a guy who was a human being, had to learn to play an instrument, develop his reputation and had ideas about what he wanted to do with his music, we better understand him.”

Many people who write program notes also tend to focus on the formal organization of the music.

“Ninety-nine percent of the people in the audience have no clue what they’re talking about,” said Loranger. “It’s like talking about math by using differential equations. Unless you’ve studied that, it’s going to be meaningless. My audience is somebody that’s got some education and is not a musician, but is interested in music.”

In his program notes, Loranger occasionally will mention an unusual part of a symphony that would be of general interest.

“But I try not to tell people how to listen to music,” he said.

In addition to writing the program notes for the Dayton Philharmonic’s Classical series, Dennis Loranger has written program notes for the Yellow Springs Chamber Music series.

Loranger’s head is filled with interesting musical history, much of which never finds its way into program notes because it may not be pertinent to the music being played.

For example, Loranger said the Nazis tried to diminish German composer Felix Mendelssohn’s fame when they came to power because of his Jewish heritage. They removed his statue from Leipzig and destroyed it.

“Mendelssohn was hugely important in the history of German music. He promoted all of these old German composers, like Bach,” said Loranger. “The reason Bach has such a huge reputation is partly because Mendelssohn was looking back at this guy who had been mostly forgotten. He started doing these performances of Bach’s music. That resulted in a century-long rehabilitation of Bach started by Mendelssohn.”

In addition to being a musician and music lecturer at Wright State, Loranger is interested in writing and poetry, which he also writes. That gives him a way with words in crafting program notes.

“I definitely had to learn how to write program notes, and occasionally I still struggle with what to write about,” he said. “When I first did it, I focused a lot more on the pieces. Now it’s more about the composers. I also like to talk about why people might be interested in these pieces to begin with.”

For example, in his Second Symphony, written on the 300th anniversary of the 95 Theses of Martin Luther, the German monk whose questioning of Catholic dogma led to the Protestant Reformation, Mendelssohn incorporates references to Lutheranism and Lutheran musical traditions.

“If you’re a Lutheran listening to this piece, you might say, ‘Oh, I recognize that tune’ because it be something they would have sung in church,” said Loranger. “A lot of Protestants have this repertory of hymns they are all familiar with. They’ve been singing them all of their lives.”

When Loranger is assigned to write a program note, he begins to research the composer and the work. He relies heavily on the encyclopedic New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians and IMSLP.org, an international library of musical scores.

“I usually listen to the piece and follow the score,” he said. “Then I’ll go to the library and just start pulling books off the shelf.”

Loranger grew up in Nevada and Montana. He earned his bachelor’s degree in music from University of Nevada, Reno, and then studied guitar and music history at the University of Idaho, where he received master’s degrees in music performance and music history. He earned his Ph.D. in music history from the University of Colorado.

Loranger later became interested in physics and was halfway toward earning his bachelor’s degree in that major when he was hired by Wright State in 2007 as a lecturer in music. He teaches music history courses in the Medieval, Baroque, Classic Romantic and post-1900 periods. He also teaches a Great Books class for the Department of English Language and Literatures.

In his nearly 10 years of writing program notes, Loranger said the most amazing piece he heard and wrote about was “Stimmen… Verstummen…,” a symphony in 12 movements by Russian-Tatar composer Sofia Gubaidulina.

“It was a challenging piece,” he said. “I had listened to it several times before the concert so I knew what was coming. But it was really powerful. I thought the philharmonic did an amazing job.”

Glowing grad

Glowing grad  Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus

Wright State’s Homecoming Week features block party-inspired events Feb. 4–7 on the Dayton Campus  Wright State music professor honored with Ohio’s top music education service award

Wright State music professor honored with Ohio’s top music education service award  Wright State’s Industrial and Human Factors Engineering program named one of top online graduate programs by U.S. News

Wright State’s Industrial and Human Factors Engineering program named one of top online graduate programs by U.S. News  Student-run ReyRey Café celebrates decade of entrepreneurship at Wright State

Student-run ReyRey Café celebrates decade of entrepreneurship at Wright State